“That time of the month” can mean many things to a menstruating woman: prime time to conceive, the start of a period, or maybe a noticeable change in the quality of her sleep. In this post, we’ll explore the ebb and flow of different hormones across the month and how they cause physiological changes that affect everything from energy levels to mood, gut function, water retention, and pain sensitivity. Most importantly, we’ll look at how these hormones also drive unique changes to sleep stages, nighttime awakenings, and how likely a woman is to snore.

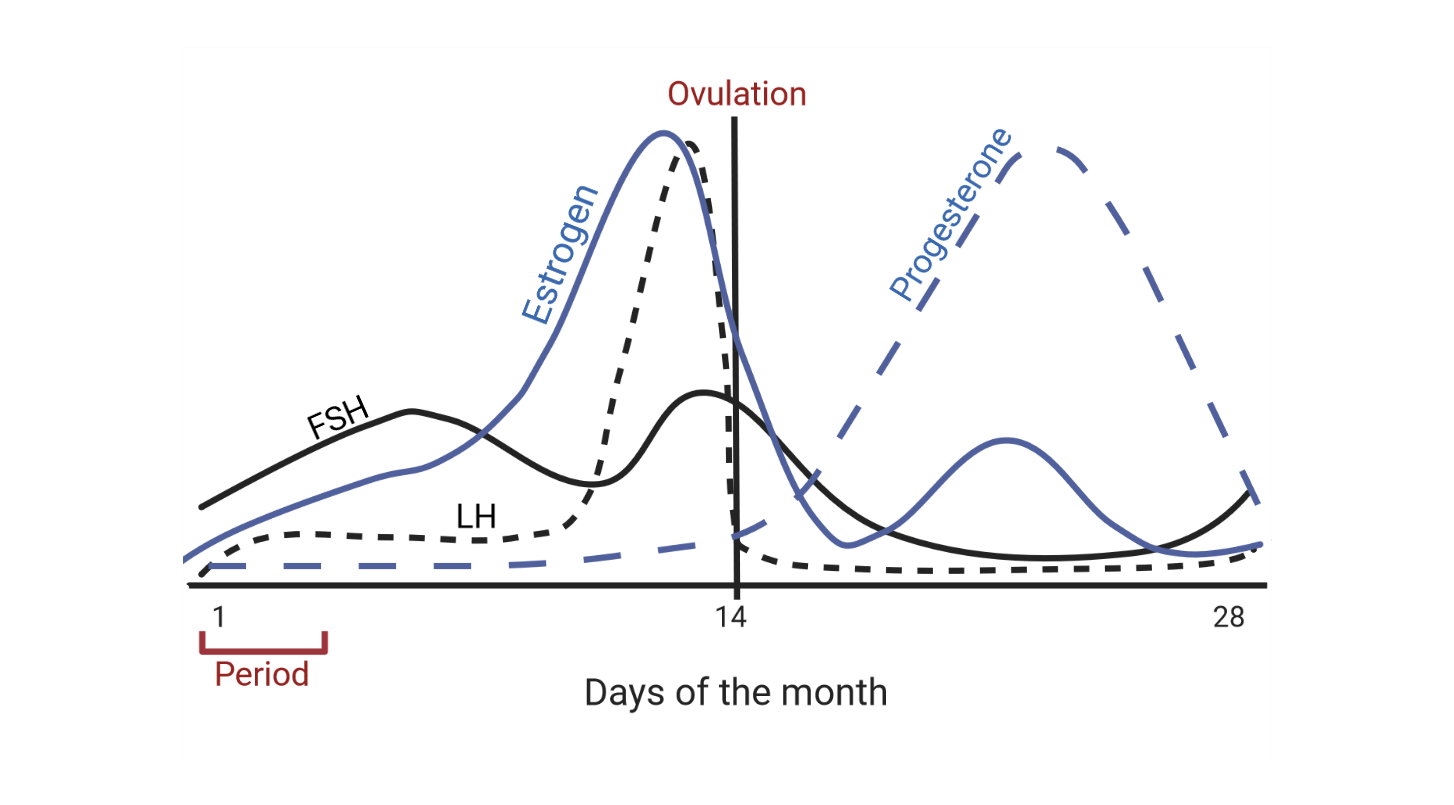

Before we dive into the interplay between hormones and sleep, let’s first get oriented with the basics of the menstrual cycle. Over the course of approximately 28 days, follicular stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and estrogen stimulate the release of an egg from the ovary, known as ovulation. After it has released an egg, the egg follicle begins to degrade. This process lasts about two weeks and involves the release of progesterone aimed at supporting a potential pregnancy that may have occurred. Once the egg follicle (now called a corpus luteum) has completely degraded, progesterone levels decrease. If no pregnancy occurred, the uterus lining sheds, and a woman will have her period.

There are two distinct phases to the menstrual cycle: the follicular phase (from period until ovulation) and the luteal phase (from ovulation until the next period begins.) Estrogen dominates during the follicular phase and progesterone dominates during the luteal phase. These drive many of the changes that women experience. Generally speaking, women tend to feel happiest and most energized as they approach ovulation and tend to get increasingly fatigued as well as more likely to experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms like cramps and headaches as they approach their period.

Studies show that women typically report their best sleep in the time approaching ovulation and have their worst sleep in the lead up to and during their period [1]. There are many reasons for this, from the more obvious PMS symptoms that affect up to 80% of women, to the changes in sleep that can lead to next-day fatigue [2].

During the luteal phase, women typically get less slow-wave (deep) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep than they do during the follicular phase. They also often experience more sleep spindles, which are rapid bursts of brain activity associated with learning and memory formation. In the lead up to a period, women often find that their sleep is more fragmented, and they might report feeling less restored and sleepier the next day [1].

As long as it isn’t distressing or debilitating, the good news is that there are many strategies for alleviating discomfort around the time of menstruation. Scheduling time for rest, eating a healthy diet, drinking plenty of water, and doing light exercise can all improve mood and lessen pain. A short afternoon nap can also help to restore energy levels and make up for a bit of lost sleep. Importantly, understanding that PMS symptoms are driven by hormones, are normal, and will pass in a matter of days can be empowering and take some of the mystery out of the equation.

For women who experience more severe pain or drastic changes in mood around the time of menstruation, as well as women looking for highly effective ways of preventing pregnancy, hormonal birth control (HBC) may be an option. Whether it’s in the form of a pill, intrauterine device (IUD), implant, patch, or injection, HBC can improve quality of life for many women. However, it’s important to note that HBC also affects sleep.

HBC works by suppressing the natural ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone over the course of the month. Instead, it provides a steady dose of synthetic progestins (to mimic progesterone) and often synthetic estrogen too. These drugs put the female body into a state similar to the luteal phase in naturally-cycling women and the effects on sleep are somewhat similar [3]. Sleep studies demonstrate that women on HBC experience less deep sleep and more sleep spindles. But they also often experience more REM sleep compared to non-HBC users in the luteal phase [4].

It’s important to keep this in mind because our sleep needs change throughout our lifetime. Deep sleep is important for development in early life, and then rest, repair, and brain health in adulthood. The amount that a person gets typically decreases with age, replaced with more stage 2 sleep, which is somewhere between light and deep sleep. Sleep spindles are an important characteristic of stage 2 sleep and are associated with learning and memory formation, but also depression in some individuals [5]. REM sleep – when dreams happen – is associated with emotion processing and forming certain types of memories.

What these changes to sleep mean as a result of HBC are not fully understood, but the suppression of natural hormones is associated with depression, anxiety, certain cancers, blood clots, stroke, and migraines in some individuals and must always be discussed with a doctor [3].

HBC can be helpful for women who experience sleep apnea, which is a condition where the muscle relaxation that occurs during sleep narrows the airways and makes breathing more difficult [6]. Typical symptoms include snoring, pauses between breaths, and sometimes even waking up choking or gasping for air. Progesterone is a potent breathing stimulant that keeps the airways open during sleep. During the luteal phase in naturally-cycling women, as well as in HBC users that take synthetic progestins, the risk of sleep apnea and snoring decreases. Synthetic progestins taken by postmenopausal women in the form of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) also offer the same protective effects.

Why a woman's sleep changes throughout the menstrual cycle, among individuals using HBC, is not well understood and needs further research. In particular, we don’t know how HBC influences long term sleep health, but regular check-ups with a trusted physician is the best way of monitoring any changes.

Non-HBC users can optimize their sleep by tuning into what their bodies need at different times of the month. In the time preceding ovulation when energy is highest, more intense exercise is often easier and more enjoyable. Sleep also tends to be less challenging. In the lead up to menstruation, it’s natural to feel more tired, but maybe struggle with a bit of insomnia. Anticipating what might come next is the best way to offer support and self-care for total mind and body health.